How Spexigons Work: The Science Behind Standardized Aerial Data

Why does a decentralized aerial data network need hexagons instead of squares or arbitrary boundaries?

Traditional aerial imagery suffers from inconsistency.

This inconsistency makes the data nearly useless for applications requiring comparison across geography or time.

Coordinating thousands of independent pilots requires a system where everyone produces compatible output without constant supervision.

Hexagons solve a geometric problem: how to divide any geographic area into uniform zones that minimize edge effects and optimize coverage.

Unlike squares, hexagons have equal distance from center to all six edges. This means a drone flying from the center can reach any boundary in the same time and battery consumption. Flight planning becomes predictable.

Hexagons tessellate perfectly—they tile across any geography without gaps or overlaps. Their six-sided symmetry means each zone has consistent relationships with neighbors, simplifying data processing and zone assignment.

This isn't novel geometry. Uber developed the H3 spatial indexing system using hexagons for exactly these properties. Nature uses hexagons (honeycomb) for the same reason: optimal space-filling with minimal material.

Why are Spexigons as big as they are? Battery physics and regulatory constraints.

Sub-250g drones like the DJI Mini series run 25-30 minutes per battery under ideal conditions. Wind, cold, and altitude reduce this. A safe mission needs buffer for takeoff, landing, and return-to-home reserves.

At 80 meters (262 feet) altitude with standard overlap requirements for photogrammetry processing, a 25-acre Spexigon requires roughly 7-8 minutes of flight time. This leaves comfortable margins within a single battery while maximizing coverage efficiency.

Larger zones would push battery limits or require swaps mid-mission. Smaller zones would be inefficient—too much time on takeoff and landing relative to capture.

The sub-250g drone class matters because many countries classify these micro-drones as low risk, allowing pilots to fly with fewer operating restrictions. They're quiet, widely available, and have global distribution with millions of units sold worldwide.

You might be wondering why the size of a Spexigon can vary if they’re standardized. When you project a hexagonal grid onto a sphere (Earth), the hexagons can't all be perfectly identical in area. And, as you move toward the poles, the meridians (longitude lines) converge. A hexagon that's 1 kilometer edge-to-edge at the equator covers more actual ground area than the same 1km edge-to-edge hexagon near the North Pole, because the Earth's surface is "wider" at the equator. So while a Spexigon near the equator might be 28 acres and a Spexigon in Northern Canada might be closer to 22 acres, they still work as part of the same standardized system.

Each Spexigon has identical specifications.

Altitude: 80 meters (262 feet) AGL (Above Ground Level). This produces sub-inch ground sampling distance with modern micro-drone cameras—sufficient for most analysis use cases while maintaining flight efficiency and regulatory compliance.

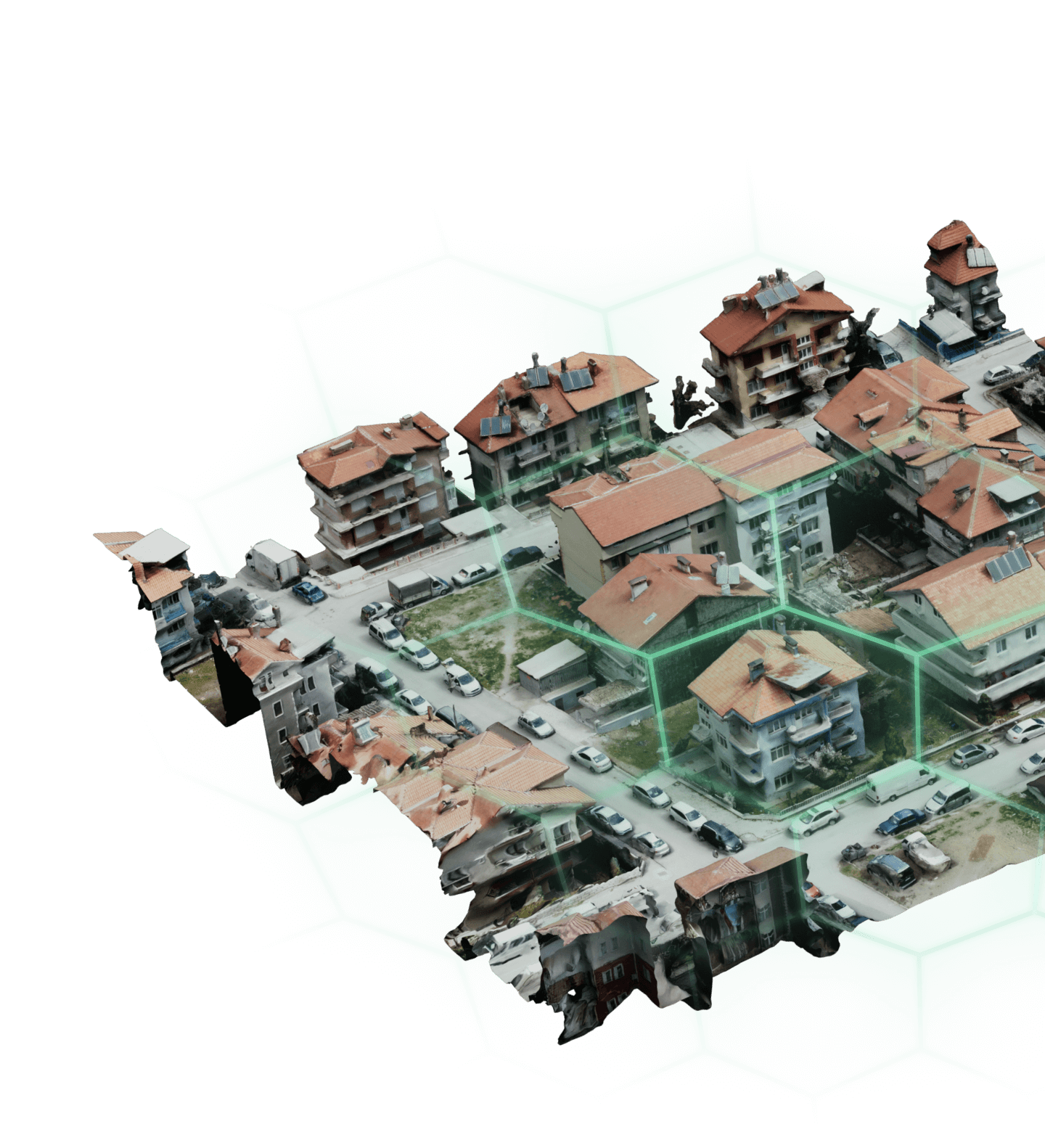

Overlap: Automated flight planning ensures proper frontlap and sidelap between images. Photogrammetry software needs redundant perspective to build accurate 3D models and orthomosaics.

Image Quality: Minimum resolution thresholds, focus verification, exposure requirements. Images must be sharp, properly exposed, and contain valid GPS metadata.

Metadata: Every image timestamp, GPS coordinates, altitude, camera parameters. This enables temporal analysis and automated quality verification.

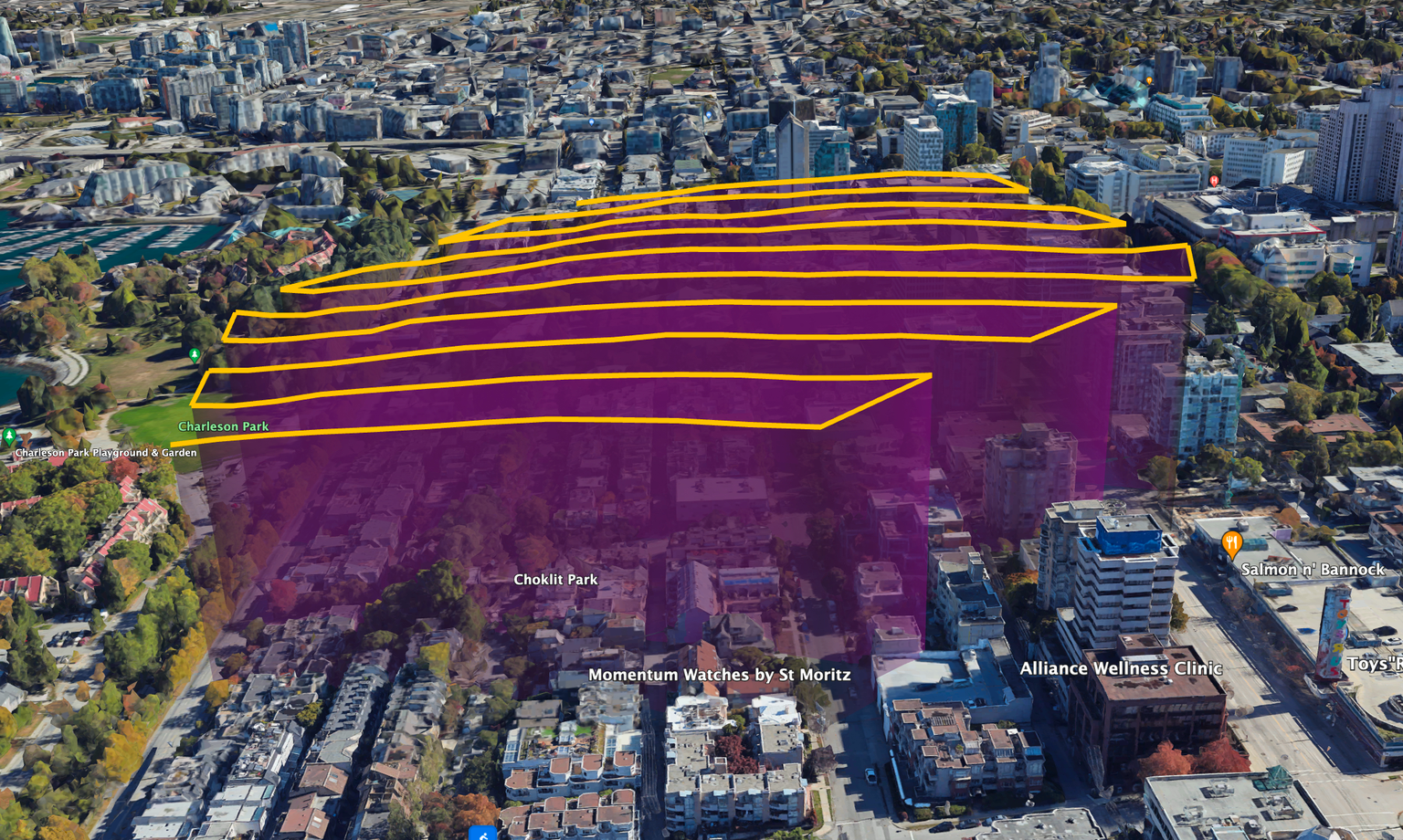

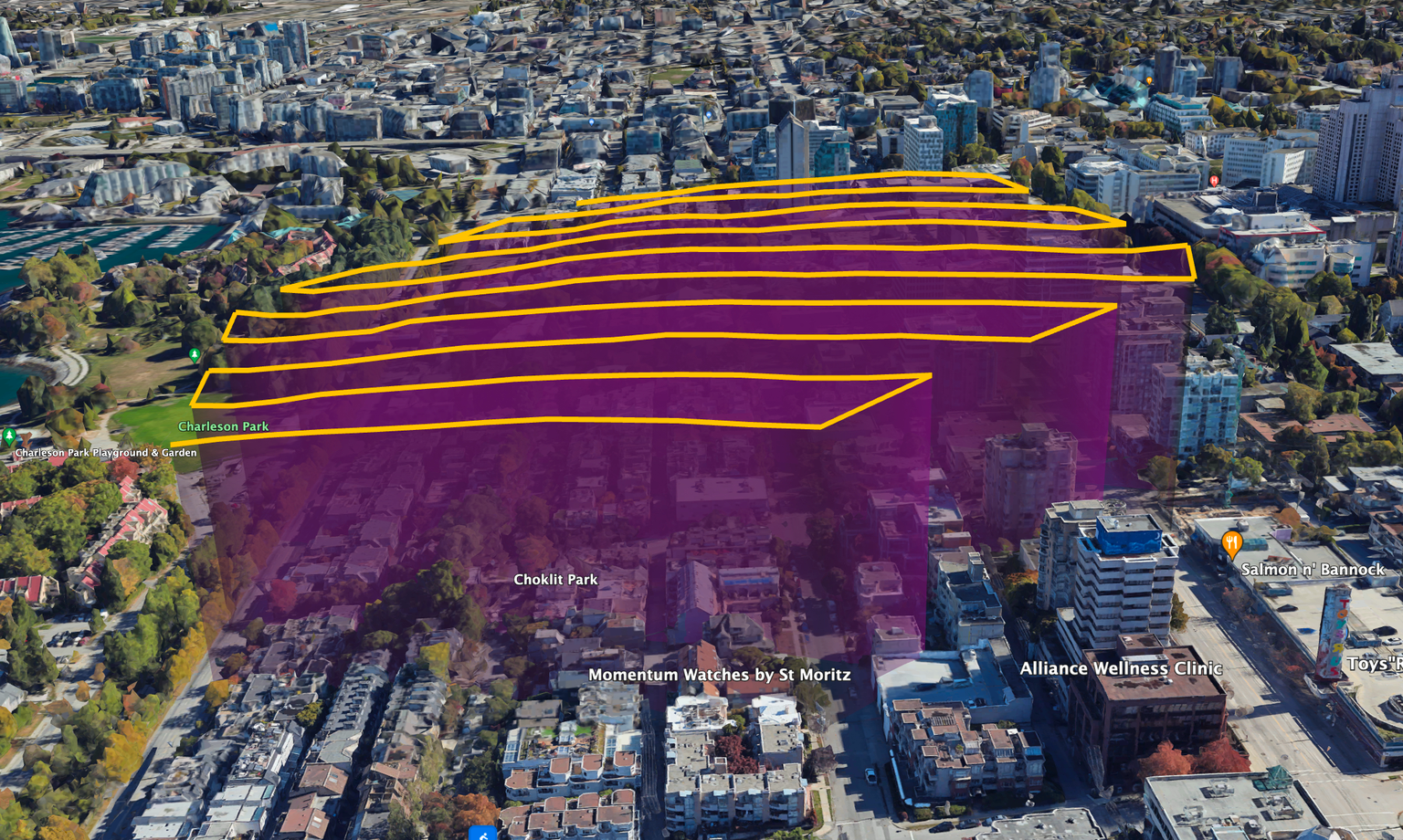

Pilots don't choose these parameters—the Spexi app flight planning system enforces them automatically. A pilot initiates the mission; the drone executes the standardized capture pattern autonomously.

Standardization transforms individual flights into network infrastructure.

Automated processing pipelines can ingest any Spexigon capture with identical workflows. No custom handling per pilot or region. This makes per-zone processing costs approach zero at scale.

Temporal datasets emerge naturally. When three pilots capture the same Spexigon across different months, the standardized format enables immediate comparison. Change detection algorithms run automatically—no manual alignment required.

Multiple pilots can cover adjacent Spexigons without coordination. The standardized edges align perfectly, creating seamless mosaics across regions.

Most importantly, Spexigons create a data primitive—a standardized building block that applications can depend on. Developers build tools knowing exactly what data format, resolution, and metadata they'll receive. This is what turns aerial imagery from custom deliverable into an infrastructure layer.

Compare to early internet: HTTP standardization made the web possible. Before that, every service used proprietary protocols. Standardization enabled composability.

The specifics of a Spexigon are standardized at scale. This standardization is what makes decentralized coordination possible. Without it, you'd have thousands of pilots producing incompatible data. With it, you have infrastructure.

In 2025, LayerDrone achieved 40,000 community members and awarded 1.4M XP for their contributions.

In 2025, pilot contributors 10x'd while network coverage expanded by 307% YoY.